-

Energy Never Dies: Afro-Optimism and Creativity in Black Chicago

Energy Never Dies Afro-Optimism and Creativity in Chicago outlines the undefeatable culture of Black Chicago, past and present.

-

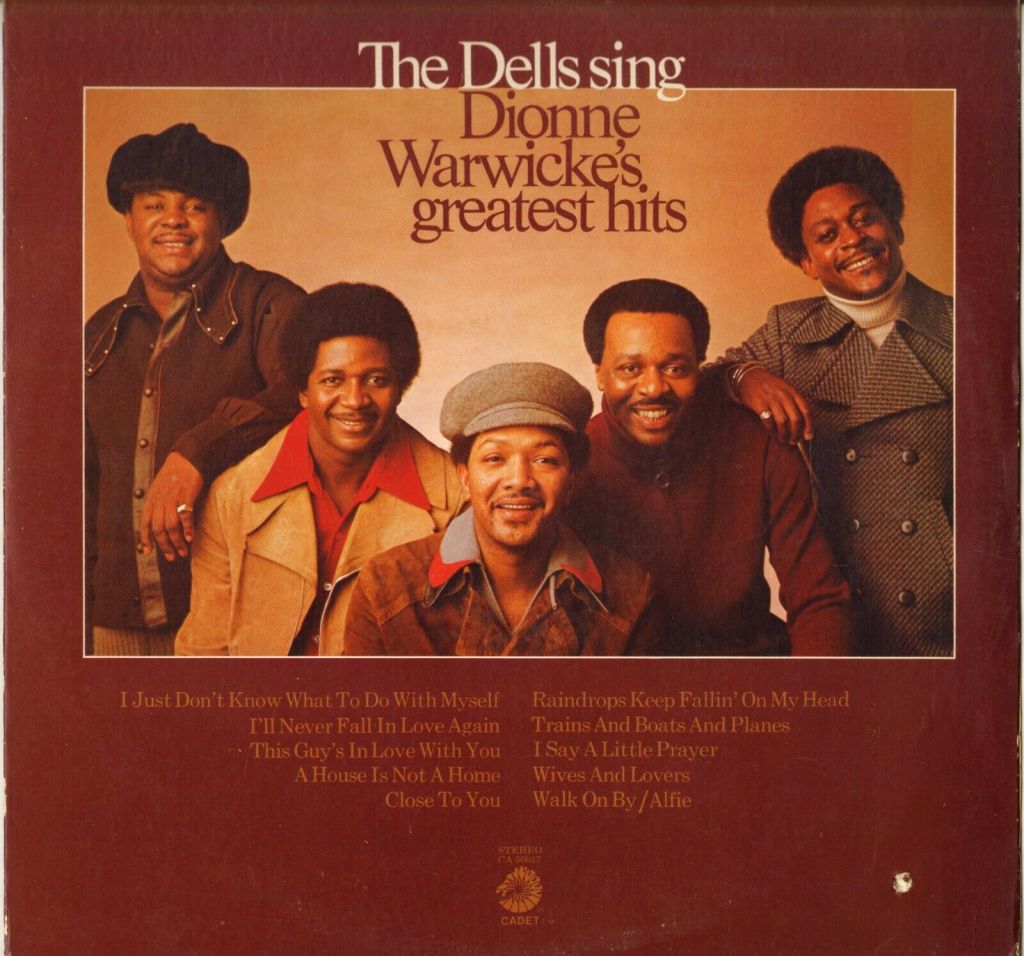

Charles Stepney in Full Flower

Ayana Contreras Recorded January 26, 1972 at RCA Studios in Chicago, The Dells sing Dionne Warwicke’s Greatest Hits is an album that features nearly a dozen of Charles Stepney’s magical reimaginings of Burt Bacharach/Hal David compositions. On the as-released version of the album, idiosyncratic Dells baritone Marvin Junior growls pleasingly (in concert with the rest…

-

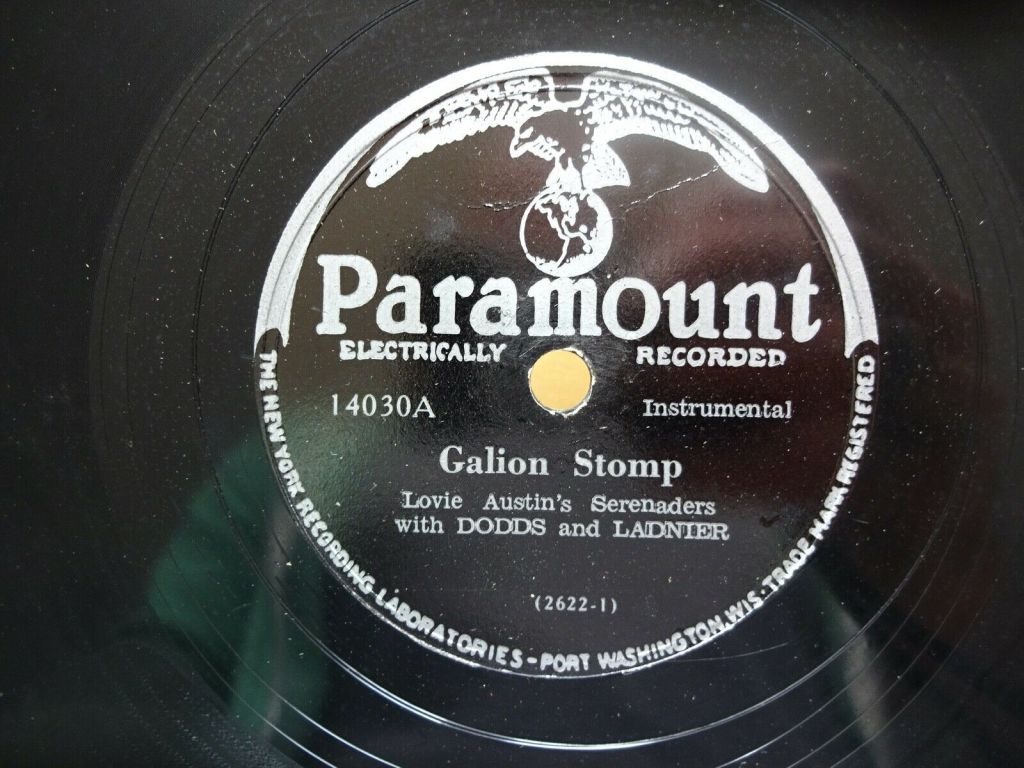

Lovie Austin: Got The World In A Jug

Lovie, like Ma, relished in crafting her presentation. Unlike Ma, she mainly worked in the background, supporting Blues vocalists like Ma Rainey, Alberta Hunter and Ida Cox, while leaving an outsized impression on those who dared to glance beyond the spotlight.

-

Eddie Sings The Blues

Chicago saxophonist Eddie Harris is perhaps best remembered as an unabashed experimentalist, famously playing the Varitone electronic saxophone on albums like Plug Me In (1968). He also utilized an early tape looping mechanism (now so en vogue) on 1969’s Silver Cycles. So, Eddie Harris Sings The Blues (1972) stands less as an outlier than as…

-

Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago through a kaleidoscopic lens

Installation view, Duro Olowu: Seeing Chicago, 2020. Photo: Kendall McCaugherty. The Seeing Chicago exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago(curated by Duro Olowu), immediately bombards you with powerful works by Chicago-bred artists. AfriCOBRA and Judy Chicago alongside Amanda Williams. But what it offers is even more than that. It’s a reflection of Chicago’s kaleidoscopic…

-

Ayana Contreras Shares Her Mid-Year Best of Chicago Music 2019

Ayana hosts Reclaimed Soul on Vocalo and WBEZ and co-produces Sound Opinions on WBEZ. She also can’t stop digging… Top Chicago Releases of 2019 This has been an incredible year for Chicago music, so far. Here’s a short list of releases I’ve fallen for: The Oracle – Angel Bat Dawid (International Anthem) This woman’s bright and…

-

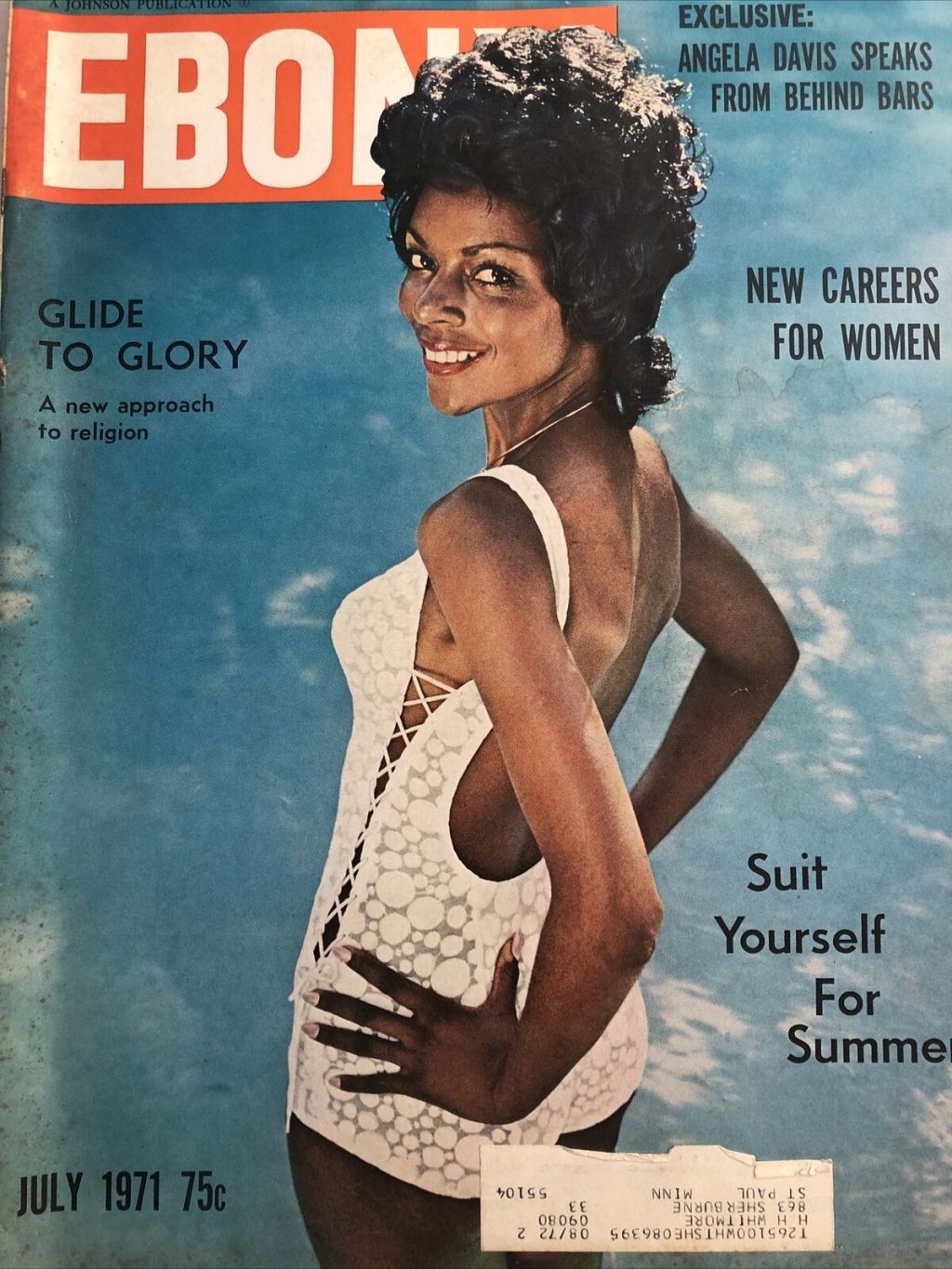

Devin Mays of Rebuild Foundation on the lasting legacy of black media giant Johnson Publishing

Reclaimed Soul host Ayana Contreras in conversation with Devin Mays of Rebuild Foundation about the legacy of Ebony Magazine, Jet Magazine, & Fashion Fair Cosmetics, as well as A Johnson Publishing Story (an exhibit at Stony Island Arts Bank). For more the legacy of Ebony Magazine (and its parent company, Johnson Publishing Company), click here.…

-

Linda Clifford and Richard Steele on Reclaimed Soul Live 2018

A tribute to classic Chicago radio station WJPC (Ebony/Jet’s radio station) hosted by Reclaimed Soul host Ayana Contreras with former WJPC program director Richard Steele, an interview with Chicago disco/soul legend Linda Clifford (“Runaway Love”, “If My Friends Could See Me Now”). We hear vintage WJPC audio including Richard Steele back in 1974 and Linda…

-

1968: In Wake of King’s Slaying, Black Chicago was Cloaked In Grief, In Song

In April of 1968, an uprising lit up the West Side of Chicago in response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. Black Chicago had a special connection to the civil rights leader: Dr. King lived on the West Side in 1966, fighting along with the Chicago Freedom Movement for open housing. Reclaimed Soul…

-

Reclaimed Soul: Cuba / Chicago Connections

Okra made the Trans-Atlantic journey on slave ships alongside human cargo. The fact that the fuzzy green seed-laden vegetable is eaten by black folk in the United States is a miracle. A vegetable umbilical cord. But to see okra in Cuba was a metaphor for a very particular shared narrative. One of survival. One of…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.