Reviews

-

Stretching out the Boundaries of Jazz: 10 years of the Hyde Park Jazz Festival.

The Hyde Park Jazz Festival celebrates its 10th Anniversary with three dozen performances and programs on 11 stages across the neighborhood this weekend. Many of the performances, to their credit, lack easy categorization, and truly exemplify the spirit of Jazz from the South Side of Chicago (multi-layered, collaborative, and connected to the community).

-

A bit about Black Rock Bands out of Detroit.

This weekend at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, I caught a documentary about Death, a 1970s all-black proto-punk band out of Detroit. The documentary, titled “A Band Called Death” chronicled the group’s forming, brush with success, and descent into obscurity. The master tapes of their sole album, recorded under Don Davis’ Groovesville productions languished…

-

Passing Strange: a righteous afro-rock opera comes to Chicago!

“Passing Strange“, the Tony-winning black rock-opera is righteous, and it’s being staged in Chicago featuring local soul revivalists JC Brooks & the Uptown Sound… and my chica: LaNisa Frederick. Amen. Passing Strange is the coming-of-age story of “Youth” (Daniel Breaker), a kid growing up somewhere in LA in the seventies. He is disillusioned because he doesn’t fit the common…

-

In the Blood: susan lori parks’ remix of “scarlet letter” in chicago

“My life’s my own fault. I know that. But the world don’t help.” — Hester La Negrita “In the Blood”, the “bold re-imagining of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s masterpiece, The Scarlet Letter, embraces the yearning for love, family, and the price of moral absolutes” according to the UIC Performing Arts website. The rework centers on Hester La…

-

Under the Spell of Red and Brown Water

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “In the Red and Brown Water,” now playing at Steppenwolf’s Upstairs Theater, is an exercise in duality that lends itself to complete immersion, an exercise in which you’re left like a used bag of orange pekoe (feeling purposefully spent). Reality blends with chorus-driven fantasy, magic with carnality, and comedy with tragedy in this…

-

Passing Strange: a righteous afro-rock opera

“Passing Strange“, the Tony-nominated black rock-opera is righteous…. Amen. Passing Strange is the coming-of-age story of “Youth” (Daniel Breaker), a kid growing up somewhere in LA in the seventies. He is disillusioned because he doesn’t fit the common definition of blackness. Floating above the city, getting high in his choir director’s blue Volkswagen beetle, “Youth” decides to…

-

Hey, White Girl! Susan Gregory’s Chicago Story

The intersection of race and class. In Chicago. In the late 1960s. That’s the backdrop of a memoir (rather cheekily) titled “Hey, White Girl!” written by Susan Gregory (Norton, 1970). In the book, teenage Susan transfers from well-heeled, suburban New Trier High School to attend infamous-even-then Marshall High School on Chicago’s West Side for her senior year.…

-

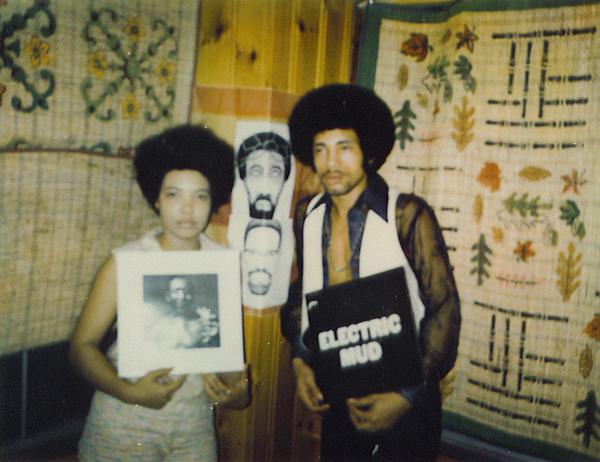

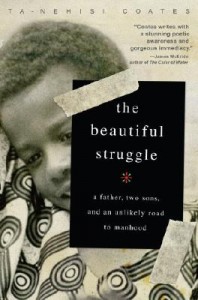

Another Beautiful Struggle

“We took comfort in the rebel music that was pumped into the city from up North. Hip-Hop was the rumble of our generation, unveiling all our wants, fears, and disaffections. But as the fabled year of ’88 came upon us, we saw something more in the music, a deeper thing that interrogated our random lives…

-

The Other Side of Paradise, in plain view

Poet Stacyann Chin’s memoir, “The Other Side of Paradise” (Scribner, 2009), is a coming-of-age story. It’s a tale of growing up never fitting in, not with family, not with social structure. It’s also about living in Paradise (both literally and figuratively), but never feeling as though Paradise’s bounty is available for you. Ultimately, however, the book…