Black Literature

-

avery r. young: local wordsmith publishes opus on facebook

Avery R. Young, local Chicago wordsmith, educator, personality, and friend of darkjive, is in the midst of publishing a series of thirty works (some poetry, some script treatments, and some more visual pieces) in the form of facebook notes. The work plays with notions of language, blackness, and the canon of African-American pop culture as…

-

Ronald Fair: Griot of Chicago Tales

1932— Ronald Fair is perhaps best known as a teller of crisp, satirical, and unsentimental Chicago Tales: inner city stories of struggle, morality, and overcoming (not unlike his own Chicago story). Born in Chicago on October 27, 1932, Fair attended public school. He was inspired as a young man by fellow Chicagoan Richard Wright to begin writing.…

-

Another Beautiful Struggle

“We took comfort in the rebel music that was pumped into the city from up North. Hip-Hop was the rumble of our generation, unveiling all our wants, fears, and disaffections. But as the fabled year of ’88 came upon us, we saw something more in the music, a deeper thing that interrogated our random lives…

-

Into Africa: 50 must reads for “Every African”…

…courtesy of afripopmag.com… lots of good stuff for a book nut like me. Anthem of the Decades, by Mazisi Kunene. Biko, by Donald Woods Roots, by Alex Haley Number 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, by Alexander McCall Smith Long Walk to Freedom, by Nelson Mandela Things Fall Apart, by Chinua Achebe Woman at Point Zero, by Nawal el…

-

The Other Side of Paradise, in plain view

Poet Stacyann Chin’s memoir, “The Other Side of Paradise” (Scribner, 2009), is a coming-of-age story. It’s a tale of growing up never fitting in, not with family, not with social structure. It’s also about living in Paradise (both literally and figuratively), but never feeling as though Paradise’s bounty is available for you. Ultimately, however, the book…

-

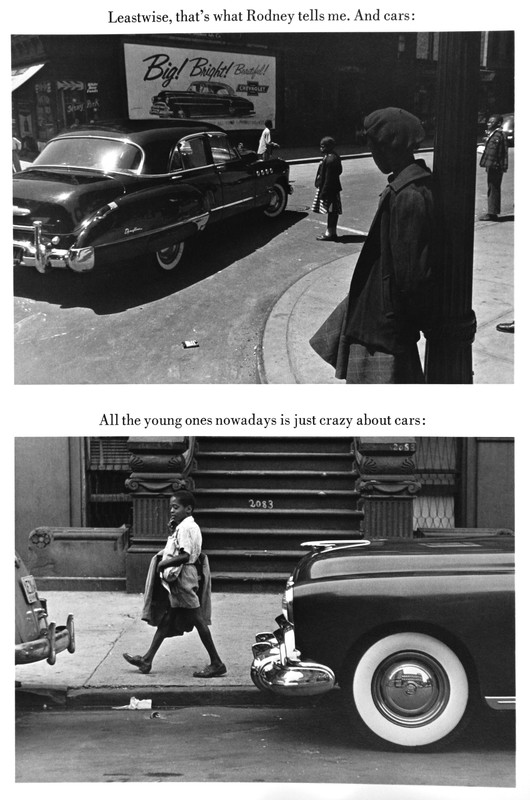

Sweet Flypaper of Life: 1950s Harlem in Black & White

Picture it. It’s the mid 1990s, I’m in high school, late for the morning bus, desperate for something to read during my lengthy commute. On my Grandmother’s disheveled porch, I find a slightly sunfaded paperback. The book is Sweet Flypaper of Life, with text by Langston Hughes and photography by Roy DeCarava (originally published in…

-

I am Not Sidney Poitier

“Not Sidney Poitier is an amiable young man in an absurd country. The sudden death of his mother orphans him at age eleven, leaving him with an unfortunate name, an uncanny resemblance to the famous actor, and, perhaps more fortunate, a staggering number of shares in the Turner Broadcasting Corporation.